Eastern Kentucky is home to three federal prisons, and the Bureau of Prisons is in the process of adding a fourth in Letcher County.

The medium-security prison would become the seventh federal prison in central Appalachia.

Taken together, the region holds 16 state and federal prisons, making it one of the country’s primary hubs of incarceration.

Former acting Federal Bureau of Prisons director Hugh Hurwitz said central Appalachia, and eastern Kentucky in particular, got this distinction thanks primarily to the work of one man: U.S. Rep. Hal Rogers.

“Congress decides when the Bureau of Prisons builds a new prison, and where they build it,” Hurwitz said. Rogers has been a member of the House Appropriations Committee since 1981, and served as committee chairman from 2011 to 2016. He’s currently chairman of the subcommittee that decides how the Bureau of Prisons spends taxpayer dollars.

“He has the ability to direct and to manage where that money comes from. And he holds a lot of power in Congress and gets people to agree with him,” Hurwitz said in an interview with KyCIR.

But despite Rogers’ efforts, local and national groups say the explosion of prisons has not brought the promised economic boom to eastern Kentucky. A new coalition made up of locals from Letcher County and formerly incarcerated activists from Washington D.C. has formed to oppose the construction of yet another Appalachian prison.

“In Letcher County and the area of Roxana, Kentucky, they are turning this into a dumping ground for all the prisoners in the continental United States,” said Wayne Whitaker, who owns property next to the proposed prison site and opposed the prison project.

This new project would add the prison and a work camp to house around 1,400 people on a former coal mine in the Roxana community of Letcher County. Rogers supports this plan for the same reasons he brought those other prisons to eastern Kentucky — he claims the prison will bring more than 300 jobs to Letcher County.

Rogers' office did not respond to a request for comment.

The Bureau of Prisons has so far refused to meet with the coalition in person. But the bureau hosted a public meeting in March, providing activists and prison supporters the first and only chance to make their case publicly to federal officials and their own neighbors in Letcher County.

At the meeting, supporters of the project reiterated claims that the prison would add jobs to Letcher County.

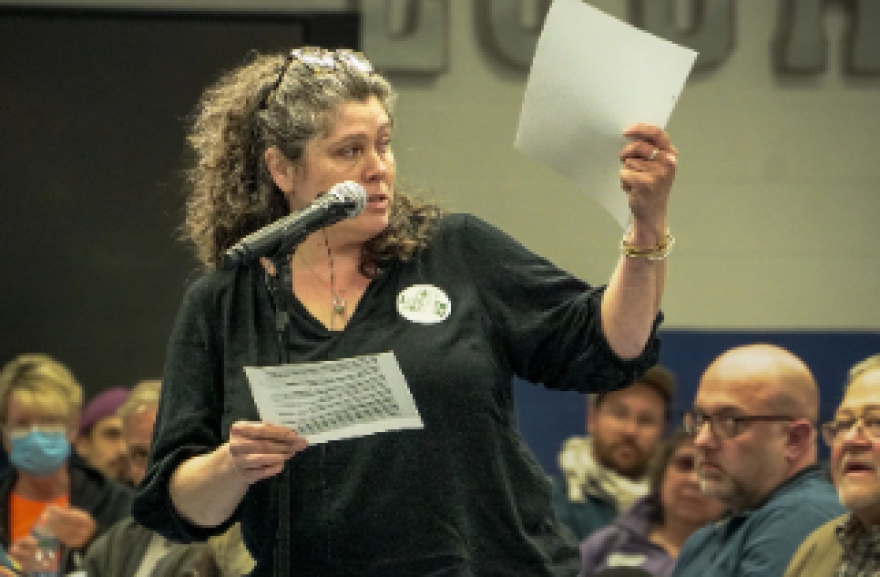

Local Amelia Kirby stood up at the meeting to push back on what she called “rosy” economic promises and call out the detrimental effects prisons have on incarcerated people and surrounding communities.

“Eastern Kentucky is an incredible place. We have unbelievable natural beauty and powerful community networks and deeply held values,” Kirby said. “We should be able to imagine a future that benefits from those factors, not from turning a dollar from the wages of human misery.”

Parkway of promise

A 94 mile drive along the Hal Rogers Parkway separates a medium security prison in Clay County, from a high security prison in Martin County. Getting to a high security prison in McCreary county takes another 19 mile drive down the Hal Rogers Parkway.

Those prisons are key parts of Rogers’ legacy as Kentucky’s longest serving Congressman.

Rogers was first elected in 1980 and served for years as chairman of the House Appropriations committee. With that experience and in his current role as chairman of the appropriations subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies, Rogers wields immense power over the federal government’s spending priorities.

In a 1998 press release, Rogers hailed federal prisons as economic life preservers as coal mines shuttered.

“We are now creating new jobs at home, stroking an economy that can change the face of our region for generations to come,” Rogers said.

But his eastern Kentucky Congressional District remains one of the poorest in the country. Economic conditions in the three counties where Rogers has brought federal prisons have worsened since the facilities were built, according to research from the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.

“Building prisons is not a jobs program,” Hurwitz said. “As a matter of fact, if prisons were to work the way society wants them to work, we would ultimately need fewer prisons, because people would come out and not recidivate.”

The Bureau of Prisons said in an emailed response to KyCIR questions that the agency considers potential job creation when building new facilities.

The draft environmental impact statement released by the Bureau of Prisons in March states that there are 90 job openings at the three prisons already operating near Letcher County. The statement says these openings illustrate the challenges the bureau faces while recruiting in eastern Kentucky and Letcher County, in particular.

“Given these conditions and the experience at other federal correctional facilities in southeastern Kentucky, only a small portion of the permanent workforce needed to operate the (prison) is expected to be filled by current Letcher County residents,” the statement says.

According to the Bureau of Prison’s own documents, federal prison employees need to be under 39 years old and pass a rigorous background check. The Bureau said it’s historically been difficult to find people in Letcher County who meet those requirements. Plus, Hurwitz said jobs in law enforcement and corrections are already struggling to attract workers.

“So, if anybody thinks that the people living in the Letcher community are going to suddenly get jobs at the prison, that's not going to happen,” Hurwitz said.

A growing opposition

For Umar Muhammad, the morning of the public hearing on the proposed prison started hundreds of miles away in a parking lot in Washington D.C. The drive through Appalachia to Letcher County filled Muhammad with anxiety.

“You got to remember last time I came to Kentucky, I was on a bus with 50 other people with handcuffs on, a belly chain on and a black box over the chain,” he said from the backseat of a van filled with 11 members of a new advocacy group called Building Community Not Prison.

Muhammad said he spent 30 years in the federal prison system, most of that time in rural prisons in Kentucky and West Virginia.

“So now I’m riding through the same dusty roads, if you will, free,” he said.

Though the prison is proposed for Letcher County, the effects of its construction will be felt in Muhammad’s hometown of Washington D.C. The prison will primarily hold people arrested in the mid-Atlantic region, and people convicted of crimes in D.C. are sent to federal prisons.

Muhammad said he came to Letcher County to share his experience with locals who are considering supporting the prison.

Lost in the discussion on jobs, Muhammad said, is the effect rural prisons have on incarcerated people and their families from far away cities.

Muhammad’s wife had to take time off work, drive long distances, endure racism and harsh treatment from prison guards to visit him in prison, he said. Keeping in touch with family so far away was hard on his mental health.

“When you come to be known as a prison town, everything digresses,” Muhammad said. “So I will travel to any length to unite with any coalition to stop them from building a prison, especially in such a beautiful town like this.”

When Muhammad and others in the van from D.C. reached Letcher County, they were met with food, music and greetings from locals who were also fighting against the prison.

That included Mitch Whitaker, who owns land adjacent to the proposed site of the prison in nearby Roxana.

Whitaker was part of a lawsuit against the Bureau of Prisons in 2017. At the time, the agency was trying to build a maximum security level prison on the same stretch of land next to Whitaker’s. The Bureau dropped that proposal in 2019. Then the agency brought it back to life in 2022 — this time as a medium security prison.

“When I first started, I thought I was in a boat out in the middle of the ocean,” Whitaker said. This time around, he’s grateful for the help from out of town. “And as you can see here today, we've got quite a turnout. So I think more and more people are being told about it.”

Back then, Whitaker was mostly concerned with the damage the prison would do to his land and property value.

“But I started learning more about once a person is placed in prison, no matter whether he committed a very serious crime or a non-violent crime or whatever, it seems like they never get out,” Whitaker said. “And their rights are stripped from them.”

The meeting

Later that evening, people gathered in the cafeteria at Letcher County Central High School for the public meeting hosted by the Bureau of Prisons.

More than 150 people attended online or in person. There were friends, neighbors and family members, some on opposite sides of the debate.

The first person to step up to the microphone was Elwood Cornett.

Cornett is a retired educator and preacher who, as chairman of the Letcher County Planning Commission, has been working to bring a prison to Letcher County for nearly 20 years.

Cornett said the project would bring “a few hundred jobs” to the area.

“I don’t know how people can be against that,” Cornett said.

By the end of the meeting, 20 people spoke in favor of the prison. Nine of those people were members of the Letcher County Planning Commission, including Sandy Hogg, another retired educator.

“I want to keep our young people here in Letcher County. We have lost a lot of our young people to traveling outside the area to get jobs,” Hogg said. “So that is my reason for being a part of this. I want them to get good, high paying jobs.”

Rogers did not attend the public meeting. His spokesperson, Danielle Smoot, reiterated claims that the prison would bring new jobs and economic activity to the area.

When it came time for Umar Muhammad to speak, he said the promises of jobs were false.

“The Bureau of Prisons, someone needs to call the Better Business Bureau because they are selling you a bill of B.S.,” Muhammad said. “This is not altruism, where they are just going to say ‘hey we’re going to take Letcher County and throw these prisons in there and let these people make this money.’”

Muhammad warned Letcher County about the downsides of being home to a prison, informed by his experience inside the bars of U.S.P. Big Sandy and U.S.P. McCreary in Kentucky.

“Don't let your community be known as just another prison county where they torture human souls at,” Muhammad said.

The very last person to speak was Letcher County resident Gwen Johnson, who came straight to the meeting from working at the Black Sheep Brick Oven Bakery, which she owns.

“I am personally insulted that this is what is being offered to our hard working people,” Johnson said. “Is this all you got?”

Johnson said other forms of economic development such as building schools or building infrastructure to improve the growing tourism industry here would be better for the county.

“We need jobs desperately,” Johnson said. “But we know we don't need something to keep people from coming into our beautiful area.”

After the meeting, prison supporter Elwood Cornett said he was convinced the prison would bring jobs, despite evidence to the contrary.

“You can’t bring 1,400 prisoners into a structure here in Letcher County without a whole bunch of jobs,” Cornett said. When asked for evidence to back up this claim, Cornett said he’d “let the future describe that.”

In his role as chairman of the Letcher County Planning Commission, Cornett is tasked with bringing jobs to Letcher County. He said Rep. Hal Rogers was a major asset in support of the prison, but he wouldn’t know where to begin bringing other forms of employment such as a factory to the area.

“I don’t know how to approach that. How do you get Toyota to build a factory here?” Cornett said. “I don’t even know who to ask for help.”

Spread the same message

Over breakfast the next morning at Johnson’s bakery, coalition members celebrated the meeting. They felt they made a compelling case against the prison, with 22 people speaking in opposition.

Before going their separate ways, coalition members discussed how to build upon their work to include communities impacted by incarceration everywhere.

“I want to go around anywhere and spread the same message,” Muhammad said. “Just like I'm concerned about Washington D.C. I've become a person who is concerned about people everywhere.”

The Bureau of Prisons will collect written comments regarding the prison until April 15. Ultimately, it’s up to the bureau to decide which comments are relevant to their proposed plan.