Amid national concerns regarding the misuse of data collected by license plate readers, the Bowling Green Police Department says it wants to improve transparency in how their network of Flock cameras operates.

Reported misuse of data, including a search for a recipient of an illegal abortion, use of AI to convert still photos to video, privacy concerns, and police sharing login information with federal immigration agents, have led to national pushback against the cameras. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) calls Flock’s network a “dangerous nationwide mass-surveillance infrastructure.”

In the Kentucky legislature, a bill introduced by Rep. TJ Roberts of Burlington would ban the use of license plate reading cameras, making their use a Class D felony. The bill is backed by 19 Republicans and two Democrats in the Kentucky House.

The Bowling Green Police Department maintains that their network of nine permanent Flock cameras, and one portable camera, has been a valuable investigative tool and does not have surveillance capabilities.

Flock and ICE

Police departments across the country have used Flock’s network to assist in federal immigration-related searches. In November, the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting revealed that a Flock account that belonged to the Louisville Metro Police Department had been used by a DEA agent to run immigration-related searches.

An internal investigation resulted in two other LMPD employees, Nicholas Owen and Jeremy Ruoff, being disciplined for similar offenses.

In Atlanta, police searched data collected by thousands of cameras across the city to track migrants, using the terms “locate alien,” and “ERO assist,” referencing ICE’s Enforcement Removal Operations division.

Bowling Green Police Department public information officer Ronnie Ward said Wednesday during an information session for the media that BGPD will not share their login information with ICE agents.

“We do not share any of our login information with any agents from ICE. Now, if there is an ICE agent somewhere in the state that has access to Flock cameras, we cannot control that because that is via Flock, not the Bowling Green Police Department. So, to say that they do not have access would be untrue, but I just don’t know the answer to that,” Ward said.

However, through their Flock network, the BGPD also has access to information from cameras in surrounding states, including Tennessee, Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois. Other agencies also have access to the data collected by BGPD’s cameras, though BGPD does not have access to a record of which agencies use their data. Department representatives said they did not know whether ICE could have access to their data with a neighboring agency’s login information.

According to Flock’s website, the company does not share customer data with any federal agency without a local agency’s choice and control.

Improving transparency

Ward said the cameras have been valuable investigative tools since their installation last year, assisting in arrests related to theft, violent crime, and crimes against children.

At the Wednesday event, Ward said the Bowling Green Police Department is disclosing the locations, key functions, and limitations of its system of Flock cameras.

The department’s cameras are focused on areas with the highest level of traffic, including Nashville, Scottsville, Russellville, Cemetery, and Morgantown roads. Ward explained that the department’s Flock cameras do not include those used by the Warren County Sheriff’s Department, the Warren County Drug Task Force, or those purchased by private retailers like Lowes. However, neighboring police departments and sheriff’s offices do share access information to each other’s Flock camera networks.

Ward said the department is seeking improved transparency regarding how the cameras operate and where they are located.

“There've been a lot of questions and social media frenzies about Flock and all of the things that go along with that, and I just want to tell you what we use them for and how we use them,” Ward said. “We don’t have anything to hide, we’re not secretively doing anything in the community with our Flock cameras that we don’t want to tell anybody about.”

In Wednesday’s meeting, Bowling Green Police said they planned to publicly share a map of the camera locations. But following the meeting, a representative said the map would not be shared.

A statement issued by the department read, “At this time, we feel that publishing the map could hinder future investigations.”

LPR Cameras

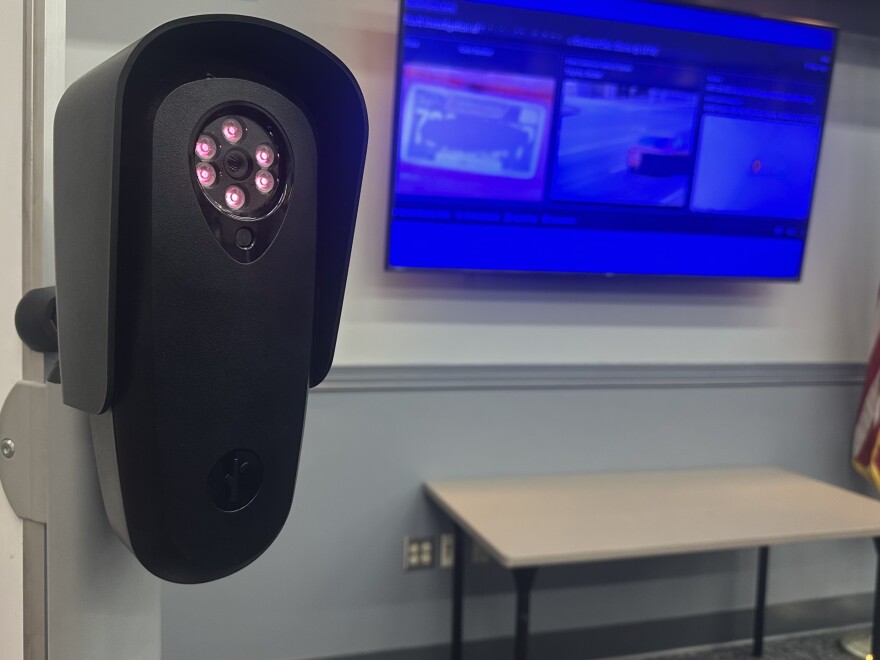

License plate reading (LPR) cameras are used in thousands of cities nationwide to assist in criminal investigations. The AI-powered cameras are used frequently by law enforcement agencies, with many local law enforcement camera networks connecting with those in neighboring states and cities to cast a wider net of potential search matches. BGPD Crime analyst JT Hickey explained Wednesday that while many companies have created and maintained LPR cameras, Flock has become the most recognizable name for the camera systems.

“It’s a lot like Kleenex and tissues, Flock cameras have kind of become a name for all license plate readers. Lots of other companies make them, but if you see a license plate reader it’s very common that in the general public we just call them a Flock camera,” Hickey said.

More than 5,000 law enforcement agencies across the country have Flock cameras, including those in Bowling Green, Bullitt County, Elizabethtown, Glasgow, Scott County, Lexington, and Louisville.

The city of Bowling Green operates roughly 425 active streaming cameras, including security cameras within community centers, CCTV cameras, and accessible streams outside businesses. That number does not include Flock cameras, which are specifically placed outdoors along the highest-trafficked areas and major intersections in the city.

Hickey said the Flock cameras are not video cameras, and do not capture a live stream. He said they are motion activated photography tools, and only store vehicle data, including plate number, make and model, color, location, and time that a vehicle was spotted. That information is deleted after a maximum of 30 days.

Hickey said there are specific criteria that must be met before that information can be legally accessed, including a case number and reason for inquiry.

“It is a wonderful investigative tool, and it is a horrible surveillance tool. We can’t live view with these cameras, we can’t use them like traffic cameras and see, like, ‘Oh, who’s traveling down Scottsville Road right now?’ We can’t do that. But after the fact, it’s really good for putting vehicles at the locations of crimes,” Hickey said.

Preliminary plans have been made to potentially double the number of Flock cameras in the city’s network.

A push for transparency

Police departments across Kentucky have been reluctant to disclose the locations of Flock cameras, arguing that providing the information would impede investigations or endanger law enforcement.

The Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting pushed for more than a dozen agencies in Kentucky, Indiana, Tennessee, and Georgia to disclose the locations of their Flock cameras. That request was met with mixed results. While some disclosed the locations, police departments in Louisville, Elizabethtown, Bowling Green, the University of Louisville, the University of Kentucky, and Atlanta, Georgia, refused to provide the requested records.

Upon their refusal, KyCIR appealed the agencies’ denials to the Office of the Kentucky attorney general. Following that appeal, staff at UK and U of L disclosed the locations of their cameras.

Appeals against other departments are still active.