Jimmy McRoberts knew the North Fork Mobile Home Park was teeming with animals. Some residents, like local grandmother Penny Gozzard, had two or three beloved cats they kept a close eye on; others let their pets roam around and mingle with the neighborhood kids who played around their families’ trailers. So when McRoberts’ entire trailer park was served an eviction notice on March 7, he realized a lot of pets were about to be left behind.

It was a gentle, breezy May evening in the small eastern Kentucky college town of Morehead, Kentucky, when McRoberts told his story outside one of the last trailers in North Fork. By this time, the park was mostly vacated, the high grasses covering left-behind odds and ends, toys and jackets and cigarette packs. Roughly 80 of McRoberts’ neighbors, served with the same eviction notice and a move-out date of April 30, were gone.

“Pets are like kids to some people,” McRoberts said. “We had such a short time that people just had to take the first available, if it was an apartment or a trailer for rent, or just move in with relatives. They didn’t have money to pay the pet deposit, or the new place just didn’t allow pets.”

McRoberts and other neighbors have rescued about 30 pets. Some have gone to their owners, but most went to shelters, or McRoberts’ new trailer, where he fosters two litters of kittens and their mothers. He’s looking for foster parents, too.

North Fork was already a fixture of Morehead when McRoberts first moved in 17 years ago, and many residents can’t remember a time without it. It’s convenient, centrally located, on a bus line. The park sits flat atop a hill, right at the entrance to the city of Morehead, abutting I-64 along Flemingsburg Road, Morehead’s main drag. Lot rents ran an unthinkably cheap $125 per month.

However, Lexington developer Patrick Madden also noted North Fork’s desirability as a location — for retail. He purchased it from its owner, Joanne Fraley, for development as a strip mall. The city of Morehead agreed in December 2020 to support the development through tax increment financing, which would funnel public money into the project, based on the principle that with business development, property values rise, sending tax revenue back to the city.

While tax revenue may benefit the low-income residents of North Fork in the future, as they compete with one another for the town’s limited housing stock, many feel it’s hard to see the bright side.

“When you [evict] 80 families at once, that’s 80 families fighting for every available spot,” McRoberts said.

Many have fanned across the region, leaving Morehead entirely for neighboring Clark County and West Liberty. McRoberts looked everywhere, even into public housing meant for the elderly and disabled, but despite a heart condition, did not qualify for public assistance, and his trailer was so old no park would take it. Outside of that, he couldn’t find rent under $1,000 per month that suited his needs. He ended up purchasing a home, but admits he was lucky. Many former North Fork residents live on unemployment or disability income. Despite owning their trailers, many, like McRoberts, had to leave theirs behind, a permanently sunk asset, too old to move.

In response, the residents had formed a campaign they called Justice For North Fork, asking for money and time to help with the move. That night, McRoberts had just wrapped up a tenants’ meeting in his former neighbor Gozzard’s trailer, which was devoid of its former comfy chairs and pictures of smiling grandchildren. Residents were relaxing, talking. Mindy Davenport crouched and smoked a cigarette on the empty lot across the road; 11-year-old Shayna Plank and her 17-year-old sister Faith had gone to bed.

Gozzard was inside with her cats, contemplating her next move. “If you’re looking for affordable housing in Morehead,” she’d said earlier, “you’re in the wroooong place.”

The cats twined around the legs of residents and they ended the meeting, as usual, in song: “We Shall Not Be Moved.” Some sang quietly, some, like Shayna Plank, shouted the words like a war cry.

The Human Toll

Tenants’ meetings have occupied much of the residents’ lives over the past month, as their campaign drew attention to the eviction and their demands: restitution for moving costs, funding to prevent housing insecurity in Morehead, and assurance that there would never again be a mass eviction in Rowan County.

Throughout April, they rallied, drawing support from throughout the state, including representatives Attica Scott and Charles Booker. Both are from Louisville, which is experiencing its own TIF-involved housing crisis.

Morehead Mayor Laura White-Brown explained the city’s rationale for the evictions in a written statement. “Along with jobs, affordable housing is also an issue for us,” she said. The city offered $1,000 to each resident in moving costs, but when it takes $3,000 to move a trailer, and often just as much to sign a new lease, many residents say that simply won’t be enough.

Other city and county officials declined to comment.

The situation in Morehead is emblematic of the limited housing options for many lower-income residents of small towns across the Ohio Valley. Though small towns and rural counties may offer cheaper housing compared to larger cities, residents of those areas often make less on average than their urban peers, while lacking urban amenities such as public transportation.

Census Bureau surveys indicate that even as the pandemic economy improves, huge numbers of people fear losing their homes. Housing advocates warn that a lack of tenant protections, rising rents, and high poverty rates, combined with the looming end of the federal eviction moratorium, leaves low-income people few options in the current housing market.

Limited Housing, Looming Eviction

Gateway Homeless Coalition works to find homes for Morehead’s homeless. Gateway uses federal funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which lists reasonable combined rent and utilities in Morehead at $625 per month and funds accordingly. Gateway often struggles to place residents at that price as rent is inflating more rapidly than HUD can keep up with, according to Gateway’s Assistant Director Paul Semisch.

“Because we’re a college town,” Semisch said, “a lot of the rental units that have been constructed over the past couple of years, the rents that are being charged are way outside the realm of the folks we serve.”

Gateway serves not only Rowan County, but also adjoining Bath, Menifee, Montgomery, and Morgan Counties. Though housing there is inexpensive, Semisch said, people with insecure housing face unique challenges in a small town with low housing stock. Many lack access to transportation and need to live near a bus line in order to work, like former North Fork resident Gozzard who does not drive and works at a minimum-wage job at the Lowe’s across the street from her old home.

The Homeless and Housing Coalition of Kentucky, a low-income housing advocacy organization, estimates that the state falls short of need by 77,000 affordable housing units. According to the coalition’s director Adrienne Bush, roughly one-third of eastern Kentuckians rent, and 68% of low-income renters are “cost-burdened.” That means they pay more than 30% of their income on rent and bills. Even when rural rent might look cheap to someone from a larger city such as Louisville, an eastern Kentucky wage still might not be enough to cover the cost.

Rowan County is in Kentucky’s 5th Congressional District, along with all of eastern Kentucky, where housing is mostly dispersed and rural. In District 5, 27% of households face severe rent burden, higher than the national average. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, a national advocacy organization for low-income renters, the largest workforce in eastern Kentucky is the service sector. In Rowan County, median service sector wages fall between $9.20 and $11.72 per hour, below the affordability threshold needed for even a one-bedroom rental, and per capita income in 2019 was $20,488.

Between health care, bills, and other necessities, some estimate Rowan Countians need to make at least $32,000 per year to make ends meet. By developer Patrick Madden’s own calculus, the average wage of his planned retail and restaurant space will range from $15,419 to $21, 753 per year.

Across the Ohio Valley, the twin troubles of looming evictions and a severe housing shortage make the future uncertain. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, in Ohio, rental units lag by 252,027, and 21% of renter households face a severe cost burden. In West Virginia 32% of renters are extremely low-income, meaning that even with unusually low housing prices, 24% of renters are cost burdened. The state lags behind the estimated need in rental units by more than 24,000.

“What we’re running into right now is just an overall lack of units,” said Rachael Coen, the chief programs officer for the West Virginia Coalition To End Homelessness. “We’re also running into hesitation from the landlords to even rent right now. Because they don’t know when this eviction moratorium is going to be over.”

Coen, whose nonprofit organization helps those facing housing crises across the state, said the rental units available on the market are either too expensive for the low-income residents they help or are not up to code for her coalition to consider as an option.

That’s especially the case in southern West Virginia, she said. She mentioned how rent for some one-bedroom units in Logan County — where about 1 in 5 live in poverty — was up to $750 a month.

“It’s comparable to what it is here in Morgantown,” she said. Morgantown is a relatively prosperous community in the north of the state, where a large research university and hospitals support many professional jobs. “The whole economic picture of southern West Virginia — who’s making enough money to afford $750 a month anyway?”

According to HUD, the fair market rent for a one-bedroom unit in Logan County is $587. That’s generally the maximum rent payment that a landlord can charge low-income residents who qualify for a Section 8 housing voucher, a federal program that usually helps pay a majority of rent for those residents. One housing advocate in the county considers some of the listed fair market rent rates as “outrageous.”

“I see the need around here. The people come in our agency all the time needing help,” said Eddie Thompson, who helps homeless veterans in Logan County find housing with PRIDE Community Services. “Seems to me like there’s not enough help to go around.”

Coming out of the pandemic, Thompson is supportive of efforts to build more housing in his rural community and elsewhere in southern West Virginia, particularly more housing that accepts Section 8 waivers. President Joe Biden’s expansive infrastructure proposal earmarks $213 billion to build hundreds of thousands of affordable housing units for buyers, along with retrofitting and building more than 1 million homes for renters. A Republican counterproposal, led in part by West Virginia Sen. Shelly Moore Capito, does not include funding for housing but instead primarily focuses on roads, broadband, and water infrastructure.

The impending end of the CDC’s eviction moratorium holds uncertainty for housing advocates and those they help.

The federal eviction moratorium, and with it the Kentucky state eviction moratorium, is slated to end on June 30, 2021. A federal judge ruled against the moratorium in early May, but the ruling was put on hold. The moratorium only covered evictions due to nonpayment of rent, meaning there were serious loopholes. As the Morehead situation demonstrates, evictions for other reasons proceeded throughout the pandemic.

Though eviction protection assistance has been available, uptake is low, as both tenants and landlords need to sign and submit paperwork for assistance to go through. Congress appropriated $21.5 billion in rental assistance in the American Rescue plan, but some say that may not be enough, or that it will not be distributed evenly among states. Bush, Semisch, and Coen all say that they are not sure what will happen when the moratorium lifts.

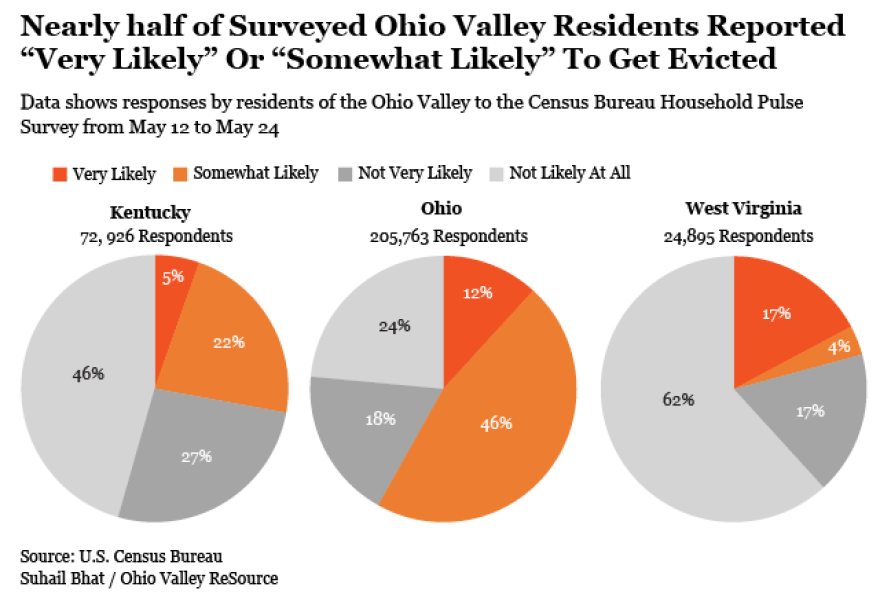

The recent Household Pulse Survey by the Census Bureau spanning May 12 to May 24 showed that nearly half of the respondents from the Ohio Valley who filled out the survey said that they are “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to lose their current home due to eviction in the next two months. A tenth of the nearly three hundred thousand respondents in the Ohio Valley reported that they were “very likely” to be evicted in the next two months.

In Ohio 58% of about 205,000 surveyed residents said they fear that they would be either “very likely” or “somewhat likely” forced out of their current home due to eviction.

About 17% of 24,895 West Virginians, 12% of 205,763 Ohioans, and 5% of 72,926 Kentuckians surveyed by the Census Bureau reported a high likelihood of being evicted in the next two months.

Mobile Home Challenges

As of 2016, roughly 12% of Kentuckians live in mobile homes, which is roughly double the national average of 5.6%. In rural Kentucky, the number is closer to one in five. In West Virginia, the number is closer to 15%. In Ohio, the number is 3.8%, but in rural Ohio, 9.1% of residents live in mobile homes.

Coen said there’s also precedent for mobile home parks closing in West Virginia, forcing residents to move and leave their tight-knit communities. She mentioned some parks have closed in recent years in Morgantown and also pointed to the closing of another park in Harrison County.

“[Mass eviction] can happen everywhere, and it does so frequently,” said Laura Knight, a community organizer for the advocacy organization Kentuckians for the Commonwealth. “It just so happens that the folks in North Fork have really been able to organize effectively around it and bring it to public attention.”

Knight said her work in the college town of Bowling Green, Kentucky, convinced her that the community hasn’t put enough priority on building affordable housing when developers might have more of an incentive to build luxury housing that could be more profitable.

Affordable options, such as mobile homes, often come at the cost of sometimes not owning the land underneath the home, as in the case in Morehead. Community engagement with their local governments is crucial for affordable housing, she said.

“Let us have the power to say what we want and make decisions in order to meet each other’s needs. I think that’s really the core of it,” she said. “We need to build housing, and so what role can our elected leaders play in ensuring that is happening?”

Uncertainty In Morehead

In late May, Mindy Davenport had news: a trailer park had finally accepted her trailer. It’s pretty far out of town, and she worries about the high costs of electricity.

“I do worry about what I’ll do next winter,” Davenport said. “I have no idea how to go about doing any of this.” Davenport said some members of the North Fork diaspora are paying for hotels while their hookups are completed, and others are simply living in trailers with no heat, no water, and no light.

Gozzard finally found a spot in an apartment just on the outer edge of town, but she was among the last to leave the park. It took a while to find anything closer under $750 per month, or on a bus line to her job at Lowe’s.

McRoberts’ bills have tripled, and the stress has taken a toll. In April, as he prepared to give a public comment about the situation at a city meeting, McRoberts had a heart attack, one he attributes to grief. That May night outside Gozzard’s’s trailer, he compared the eviction to a natural disaster.

“When you see the flipped up porches, the tall grass…” McRoberts paused and looked around. At night, the half-moon lit the old trailer hookups, the empty, bald patches of grass where free-standing porches once were. “It’s like a tornado that just went through here.”

Back at the April tenants’ meeting on the eve of the eviction, Shayna Plank thought about what home meant, in a new place where she couldn’t keep her dogs. Even though she was in the midst of her family’s move, Plank said North Fork meant more than just four walls and a lot. It was a place where her family had breathing room, she said, and it was a neighborhood.

“They try to ignore us,” she said. “Well, you can’t. You can’t, because we are the people of North Fork.” She then addressed the new property owner directly.

“You may own the land,” Plank said, “but we live on the land.”

The Ohio Valley ReSource gets support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and our partner stations.